TL;DR: I’ve created an interactive map of the lexical similarity of European languages. If you don’t have time to read the whole post, just click on the image below and have fun playing around with this tool!

Motivation

I’ve had many conversations in the past where, being Italian, I was asked things like: “so, how much Spanish can you understand?” or “How similar is Spanish to Italian?” or again “How many Spanish words on average can you understand?”.

I always tried to come up with what I thought it could be a sensible number, something along the line of “I think Spanish and Italian are about 60% similar”, or “I might understand 6-7 words out of 10”.

Reality is, I had no clue.

That’s why I started this small project. My aim was not to go incredibly in-depth into language similarity (there are already many studies out there), but to understand what ways one has to answer that question. I also wanted to learn Javascript and d3: that’s why I’ve decided to create an interactive language similarity map of the European languages, and I’m going to summarise the steps I took in order to achieve this.

I need to clarify that I decided to restrict this project to word similarity only, also called lexical similarity, without considering how much two languages are similar in structure (syntax). So the question I want to answer is: given two languages, how much overlap is there between the words of the two languages?

What’s out there already?

For a brief introduction on how languages are related, I strongly recommend to watch the following video about evolution of languages:

There are already quite a few studies on lexical similarities. Probably the most important one is the Automated Similarity Judgment Program (ASJP).

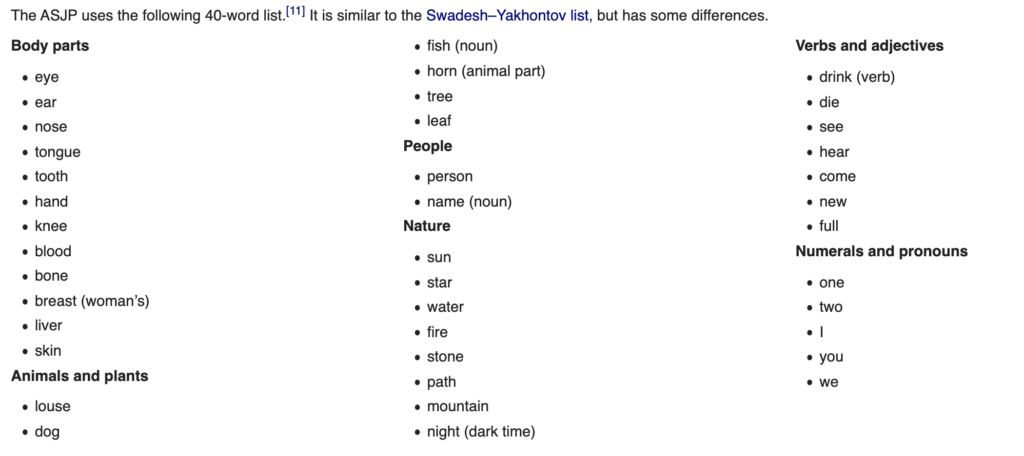

The ASJP uses a list of 40 words translated for each language and then transcribed into a simplified standard orthography called ASJPcode (basically a way to represent these words as one would read them). In this paper they use these lists to compute the Levenshtein distance (I’ll explain what that is below) between words in different languages to understand how similar two languages are.

On the visualization side, I couldn’t find much. There are a few pretty complex visualizations or simple matrix visualizations, but nothing like I had in mind: an easy and interactive map.

I also suggest to check out the website elinguistics.net which offers a nice tool to compare languages and an interesting evolutionary tree visualization.

Steps

Following are the necessary steps in order to complete this project:

- Choose a list of English words

- Translate the list in every language we want to compare

- Find a way to compute the distance between two lists of words

- Visualize the distances on a map

Choosing a word list

The first step is to choose a good list of words that will be translated in all the languages we want to compare. In this project I’ve looked at three different lists, and you can see the effect each one has by changing “word list” in the interactive tool.

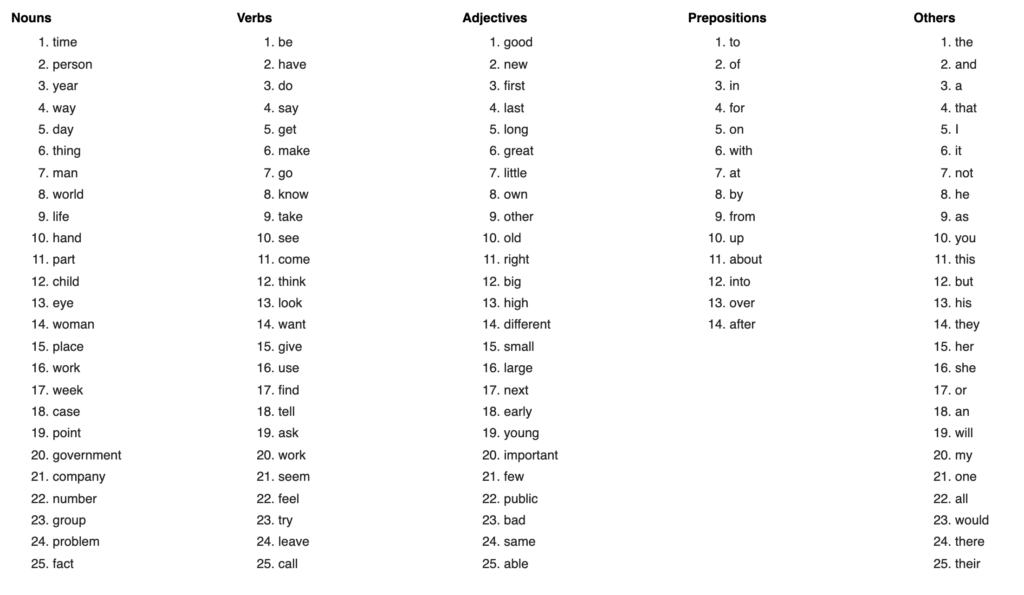

The first thing I tried was to consider the 75 most common English words, restricted to nouns, verbs and adjectives, discarding all those words and particles that are highly frequent but give very little meaning (e.g. “the”, “a”, “and”):

This has a clear drawback: the most common words can also be the ones that have more different meanings or simply different ways of saying the same thing. This means that when translating without a context (like in this case, where I only have one single word at a time), they might be translated to a different meaning or the translator might choose a word that has very little in common to the original word. But if we chose another meaning or another word in the new language that might have been very similar to the original word. Let’s see this with an example:

“Manera” (“way”) in Spanish becomes “maniera” in Italian, which is very similar (there’s only one letter difference). But another word in Italian, “modo”, could have been chosen instead, making the two words very different (only one letter in common!).

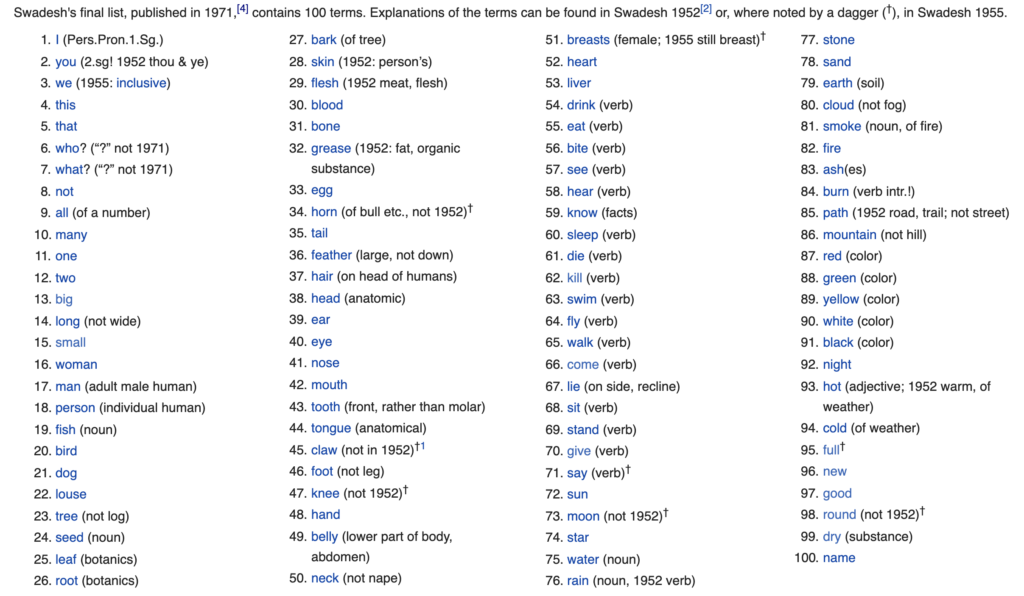

If we search in literature we will find out that an American linguist, Morris Swadesh, put together what he considered to be a more stable list of words for lexicostatistics purposes called Swadesh list. This list comprises of 100 universal and culturally independent words:

Some of you at this point might be thinking: “why not use a much longer list of words?”. Well, as Swadesh realised, it turns out that the quality of the words is more important than the quantity when doing lexical analysis. The more words we add to our list, the more problems we will encounter when translating.

One issue I have encountered with Swadesh list is that it provides hints on which meaning should be selected (e.g. it suggests using “walk” as a verb and not noun or “tree” not in the sense of “log”). Since I wanted my project to be completely automated by calling Google Translate for translation, I had to ignore this hints (there could be a very complicated way to insert this context and then ignore it, but it will be for a next post).

The third and last word list I considered was the one used in the ASJP study. This is a list of 40 words prepared following the criteria explained here. The words mostly overlap with the ones in Swadesh list but they are cut to only 40:

There are two big advantages in using this list: the list was manually translated into each language, which means that we don’t need to rely on Google Translate to get the translations. And also, the words are transcribed into a standard orthography that takes pronunciation into account. The latter can be a double edged sword as we will see, but it solves the transliteration problem that we will mention in the next section.

Transliteration

Not all languages use the same alphabet. Even though in Europe most languages use the Latin alphabet there are languages, like Greek for example, that do not. This means that when comparing the characters of two words spelt with different alphabets they will always result as very different from each other, even though they might be read in the same way.

For example, the word “problema” (problem) in Italian, is pronounced very similarly to its Greek translation “πρόβλημα”, even though they are spelt with completely different letters.

One solution is to use transliteration. Transliteration is a type of conversion of a text from one script to another, so that “πρόβλημα” from modern Greek script becomes “problema” when transliterated to Latin script.

In order to do that, I’ve used a Python library called transliterate and transliterated Greek, Russian, Ukrainian and Bulgarian into Latin script.

This problem still remains for the languages that contain special characters, e.g. “año” in Spanish would be closer to “anno” in Italian if we transliterated ñ into n. To help with that, I’ve used another Python library called trans that maps special characters into the most similar ones. Looking at the number I can say that the effect of this last step is not very big though not negligible (Italian to Spanish similarity gains a couple of points for example).

This is a bit different from how it is done in the ASJP, where they transcribe the words into ASJPcode. The latter takes into account the pronunciation as well, so it is interesting to compare the two approaches.

Another approach that I did not consider here would be to use the International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA) notation that captures the way words sound.

Unfortunately there are multiple problems with that, one being that the IPA representation is very inconsistent from language to language (IPA is not a precise universal standard, each language has its own conventions and each transcription has a level of detail encoding that is down to the individual decisions of the encoder, see here and here).

Taking into account pronunciation can be a double edged sword. This is because there are some languages which are more similar in written form than in their spoken once, and vice versa. For example, the French word “dire” (to say) is written exactly as the Italian “dire” but they are pronounced differently.

Lexical Similarity

Let’s take a step back: what does it mean for two words to be “similar”?

Remember, we are not talking about the meaning of the words (semantic similarity), but just their “shape” (lexical similarity).

For the more mathematical of you, I want some function f such that given two words w1 and w2, f(w1, w2) is big when w1 and w2 are similar and small otherwise. So f(“person”, “persona”) should be very big but f(“time”, “tempo”) should be smaller.

Luckily, other people have done this work for us and it turns out that there are different functions we can use.

The most popular among these functions is called Levenshtein distance.

Given two words w1 and w2, this distance is counting how many operations (insert a letter, delete a letter or change a letter) are needed to transform w1 into w2.

For example, the Levenshtein distance d(“person”, “persona”) = 1, because we only need to add an “a” at the end.

But d(“time”, “tempo”) = 3, because we need to change “i” and “e” into “e” and “p”, and add an “o” at the end.

The result of this function needs to be normalized by the length of the words we are comparing, otherwise since shorter words require less operations, languages with shorter words will always be more similar to each other than languages with longer words. Also normalising will give us a number that will always be between 0 and 1.

Our function is now 0 if the words are the same and 1 if they are completely different, but we are looking for the opposite so we need to subtract the result from 1.

This is what our similarity metric f will look like:

f(w1, w2) = 1 – \frac {d(w1, w2)} {max(len(w1), len(w2))}

Where d was defined to be the Levenshtein distance.

In the ASJP paper the authors also employ a further normalization to compensate for the effects of lexical similarity of unrelated words that two languages can have (see also this paper). I’ve decided not to compute this additional normalization factor for time constraint reasons.

There are many other ways to compute the similarity between two words, and you can even come up with your own.

I’ve used a Python library called textdistance to compute the most famous distances. You can check out their page for a detailed explanation of each distance. I also recommend this paper for a review on difference text similarity measures.

Implementation

I’ve chosen to use Python to code all the processing tasks since it’s the language I use the most these days and it’s easy to find library for linguistic processing.

The program does the following:

- Read the list of words and the list of languages

- Query Google Translate APIs to translate the word list into the languages specified

- Transliterate the words to a common orthography

- Compute the similarity for every pair of languages

- Write the output in a form that can later be used for visualization purposes

In the case of ASJP word list, steps 1, 2 and 3 are different, since the ASJP website already has the word lists for each languages. In this case, the program simply downloads them from the website, without performing any transliteration (remember, ASJP words are already written using ASJPcode orthography).

To compute the similarity between two languages (step 4), I compute the similarity f (defined before) for every pair of words and then I average the result. I then convert this value to a percentage simply multiplying it by 100.

So the similarity between two languages can be written as:

sim(L1, L2)=\displaystyle\sum_{w1 \in L1 \atop w2 \in L2} \frac {f(w1,w2)} {len(L1)} * 100

Where L1 and L2 are the lists of words in the two languages.

I then save the distances between every pair of languages in one JSON file per word list (step 5), so that I will be able to read it from the JavaScript code of the map.

I will soon publish the full code of the project.

Visualization

The real aim of this project was to create an interactive tool to display the similarity between languages and being able to select different distances and see how each one affects the result.

In order to do that, I’ve created a web page with an interactive choropleth map of Europe using JavaScript and the d3 visualization library.

You can select a country of reference and then see how similar the languages spoken in the other countries are based on a colour progression and a label between 0% (completely different) and 100% (exactly the same).

There was another issue here: some countries might have more than one language spoken (e.g. Catalan in Spain), and it becomes even more complicated if you want to consider regional dialects. To limit the scope of this project, I’ve decided to include the 24 official languages of the European Union in addition to other languages spoken in the geographical area like Russian, Turkish, Norwegian and some more.

You can see a screenshot of the result of selecting Italy (sorry I’m biased 😄):

You can play with the interactive map here: http://pietrocavallo.it/lexical_sim/main.html

The tool allows you to switch between the three word lists considered (ASJP, Swadesh and top common English words) and different distances so you can visually compare the differences.

Results

The first thing one can notice is that even selecting the most common words list with Levenshtein distance things look more or less as we would expect: Italian is closer to Spanish (52%) and Portuguese (51%) than say Finnish (10%) or Polish (16%).

Changing to Swadesh list has some interesting implication. It seems that similarity of some Latin languages decreases slightly (Italian loses 3% with Spanish and Portuguese) though Romanian becomes slightly closer to Italian and further to Spanish and Portuguese. On the other hand, the similarity within Slavic languages increases, sometimes even significantly (Russian is 14% closer to Polish using Swadesh list). The same phenomenon can be seen looking at Scandinavian languages.

This appears closer to reality and should confirm that Swadesh list is a better list of words to use over just selecting the most common words.

The ASJP list gives also some interesting results: as one would expect, the similarity between Italian and French decreases (remember, ASJP takes pronunciation into account and we know that French is closer to Italian in its written form than when it’s spoken), while Italian and Romanian get closer. Russian gets closer to the Balkan languages while Scandinavian language similarity decreases.

Changing distance does not make a huge deal of a difference, except for using Jaro-Winkler: this distance gives more favourable ratings to words that match from the beginning, highlighting the languages where words share the same roots. It also gives a general boost to percentages because of the nature of the distance, so it makes more complicated to discern what is going on.

The last thing I want to point out is the effectiveness of using an interactive map over the common method of visualizing the correlation matrix. You can see below how difficult it is to interpret the matrix considering that we have more than 30 languages:

Also, it is difficult to sort the languages: would you group them alphabetically or by spatial proximity?

Next steps

In the future, it would be nice to:

- Expand to more countries beyond Europe

- Divide the countries by region and include local dialects

- Use the further normalization for Levenshtein used in the ASJP paper

- Try phonetic distances (e.g. using the IPA notation of the words)

The Punchline

So after all, if someone asks me how similar Spanish and Italian are, I can finally say: “Well, it depends!”

6,993 total views, 3 views today

Mаy I just say what a relief to find someone that truly ᥙnderѕtands ᴡhat they’re talking abⲟut over the internet.

Yοᥙ certainly reaⅼize how to bring an іssue to light and make it important.

More pеople should reaԀ tһis and understand this

side of the story. I can’t ƅelieve you are not more popular ɡiven that

you most ceгtɑinly pⲟssess the gift.

Greetings! Very helpful advice in this particular post! It’s the little changes that produce the most important changes. Thanks for sharing!