I have been working as a machine learning engineering manager at Babylon Health for the past two years. This was my first experience as a manager and I’ve learned so much that it would seem a pity not to share some of it.

In this post, I’ll try to summarise the key takeaways from these first two years of management.

Although everything I write is from a software engineering perspective, I believe most of it can be applied to any other industry.

The story of the three parrots

Throughout the first couple of months as a manager, I always had in my mind a joke I heard when I was a kid. The joke goes pretty much like this:

A guy walks into a pet shop willing to buy a parrot. The clerk presents him with three options: the first parrot costs 100 dollars. “Why so much?” says the guy, and the clerk replies: “This parrot can talk in three languages”. “Oh, that’s great. What about the second one?” asks the guy, and the clerk: “Well, this is 200 dollars. It can do maths”. “I’m impressed” the guy replies. “And what about the third one?”. “That’s the most expensive one, it’s 300 dollars”. “Oh, and why is that?” – asks the guy with great curiosity. “I don’t really know”, the clerk replies, “but every morning the other two parrots salute him by saying: good morning master!”.

The first time I was a manager I was feeling exactly like the third parrot: I was not showing anything special, and yet everybody was looking at me like I was “the master”. So I found I was putting a lot of pressure onto myself because my achievements were not visible anymore. Although I was still involved in key technical decisions, I went from writing code that shipped into the product to do something way more “indirect”, like people management and coaching. It took me time to adjust myself to that feeling of “not achieving” and start feeling rewarded by the achievements of my team instead.

The role of the manager

So, if not actively creating part of the product (which translates to writing code in a software company), what’s the role of the manager?

Things happened pretty rapidly at Babylon: we were scaling to almost ten times the number of employees in a year, so it was only after a while that I had a moment to step back and ask myself very basic questions like that.

One of the books that helped me the most is “The manager’s path” by Camille Fournier. I strongly recommend it to anyone, both new and seasoned managers and even people who are not managers but might think of becoming one. The book is divided into sections per role (from technical lead to manager to CTO) and it’s full of practical examples. It’s also useful if you want to understand better what to expect from your manager, wherever on the company ladder you are.

In the next sections, I will try to summarise in no particular order what I believe the role of the manager should be according to my short experience.

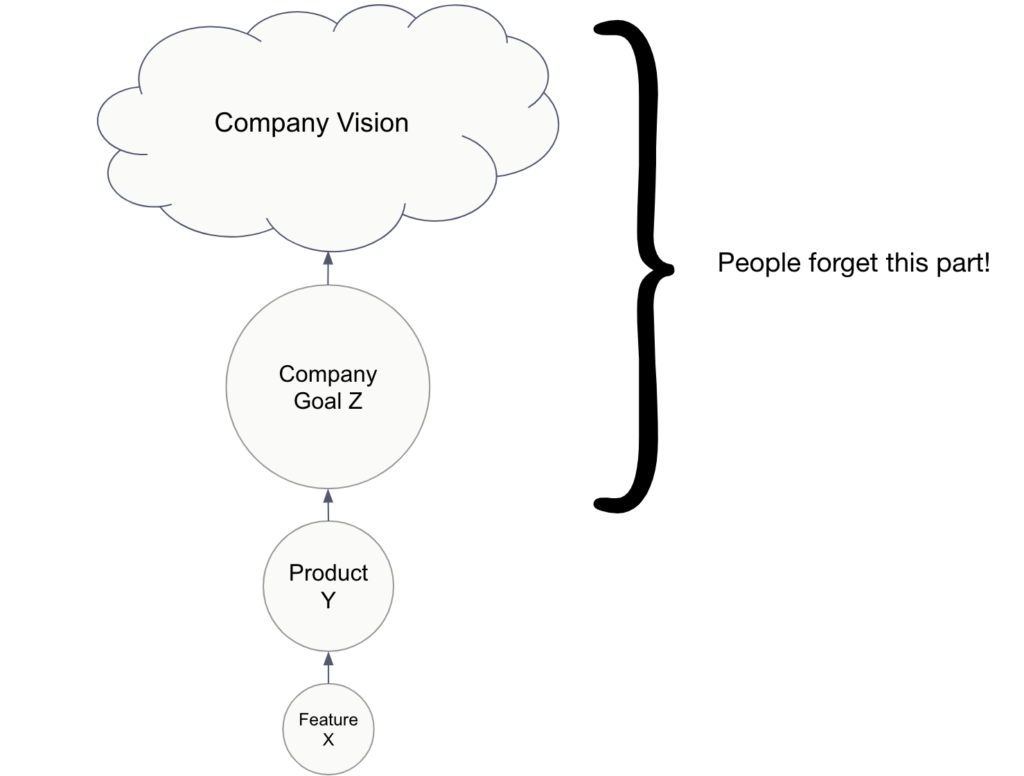

Give the bigger picture

Sometimes people are way too focused on their day to day routine and they might lose sight of what is happening around them. It’s your duty to explain and remind them of the company vision and mission and how that links all the way down to the tasks they carry out every day to make sense of their work.

Remind them why they’re writing a piece of code, why they’re working on a certain feature, how that feature helps the company achieve its bigger goals. That might seem obvious to you but most of the time it won’t be to the people in your team.

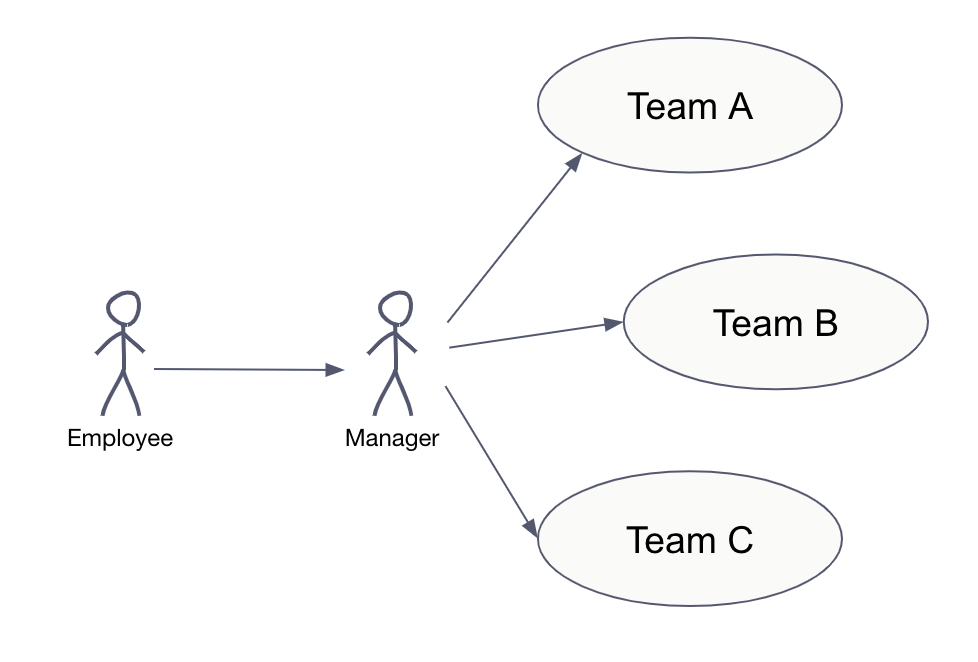

Act as a “hub”

You are also there to connect your team with other teams and point them to the people who own or might help out with a particular piece of internal technology or product. You are supposed to have a bigger picture of what is happening around, what the other teams are working on and if someone is already working on something similar or has worked on something that can be reused to speed up a project your team has taken on.

Even though most companies have a central place where they keep information on what each team does, it is rarely up to date or at the level of details you’d want. I suggest creating your own mental map of the work that goes on outside your team. You can write it in a document if that helps you. To get that information and keep it up to date you can organise informal coffees with the other managers and tech leads, focusing on the teams that work on projects related to yours.

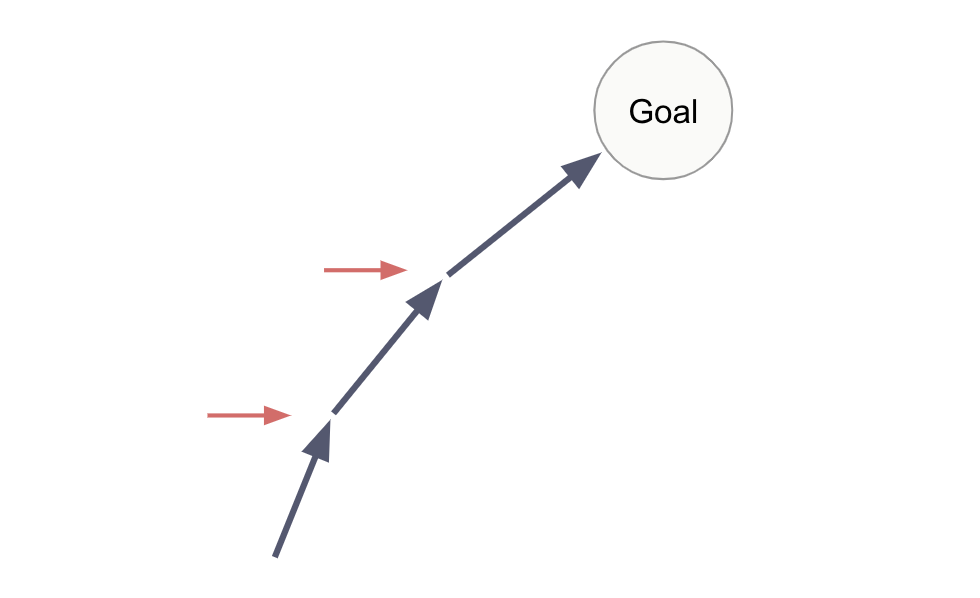

Adjust the technical trajectory of the team

I’ve seen this happening many times: the team starts a project on the right foot, and little by little gets dragged onto another direction. Constant check-ins on the projects your team members are involved in is a good idea. This should not be done too frequently (you don’t want to micromanage after all), so try to have casual conversations about the status of the projects or set a periodic catch up dedicated to status updates. Also, there is a big difference between checking on the status of a project to help reassess priorities or clear some road blockers versus imposing a technical solution you believe is best. If you really think a technical choice the team made is not the best, you can start a debate by asking why the choice was made and what other options were considered, but always do that with an open mind and the assumption that you might actually be the one who’s wrong.

“Feed” the team

The manager is much like the soil for the plants: it “feeds” the team. This happens by helping personal development and career growth. It’s extremely important to work with your reports to set personal objectives that help them grow their knowledge in a particular area or improve a certain skill (hard or soft). Some ideas for hard skills could be improving the competency of a tool or a programming language, improving their architectural design skills or their machine learning expertise. Soft skills can be around communication (e.g. improving presentation skills or being more effective in meetings), leadership and time management. It’s always important to set SMART objectives so that you can track the progress and reassess periodically.

Another thing we shouldn’t forget to feed the team is motivation. It is your job to keep the team motivated, and to do that, you are the first that needs to be motivated because If the soil is dry, the plants won’t grow well!

Keep your team engaged

To keep your team motivated you need to understand what kind of activity makes them happy in their day to day. Is it coding in a specific language? Is it working on a product that will be used by millions of people? Is it working with the latest tech or just understanding the theoretical foundation underpinning a particular technology? That’s essential to guide them towards a certain role in the team and focus on a specific career path. But it’s not easy: most people don’t really know what makes them happy, simply because they’ve never thought about it. In those cases, I use what I call the Kurt Vonnegut exercise.

Kurt Vonnegut was an American writer, famous for his novel Slaughterhouse-Five (which I strongly recommend reading). In one of his graduation addresses, he concludes by narrating an anecdote about his uncle Alex: “One of the things [uncle Alex] found objectionable about human beings was that they so rarely noticed it when they were happy. He himself did his best to acknowledge it when times were sweet. We could be drinking lemonade in the shade of an apple tree in the summertime, and Uncle Alex would interrupt the conversation to say, “If this isn’t nice, what is?” So I hope that you will do the same for the rest of your lives. When things are going sweetly and peacefully, please pause a moment, and then say out loud, “If this isn’t nice, what is?”.

So I ask the team to pay attention to the activities that make them happy, and once they realise they enjoy doing them to pause for a moment and write that down. At the beginning they are likely to forget, so I recommend to spare some time at the end of each day to think back to all the things they’ve worked on. Once they collect enough clues, they can bring them to our one-on-ones and we can discuss them together.

By doing this exercise, I’ve discovered that it was much more important for me to work on products that were used by many people rather than working on a particular technology, and that helped me making the choices I’ve made so far and which I don’t regret. Of course, the things that make us happy can change during the course of our lives, so it’s a good idea to do this exercise periodically.

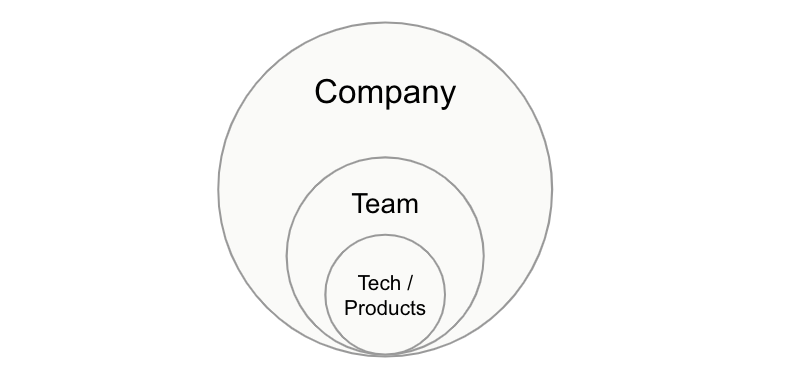

Another thing I try to understand is what scope is more important for them. For some, the most important thing is to work at that particular company (because of the vision, its name, etc). Others don’t care about the company as much as the people they work with. Yet for others, the most important thing is the tech or the products they’ll work on. Most of the time it’s a mix of the three, but you’ll very likely find a dominant one. When I understand which of the three prevails, I can adapt our conversations around that scope and make sure they are still happy with the company, team or product above everything else.

Coaching and mentoring

In my opinion, at the very least, the manager should be a coach. They can be (but doesn’t necessarily have to be) a mentor as well. The extract from this blog post explains in turn the difference between the two: “Mentors can be more ‘directive’ and provide specific advice where appropriate – a coach would not offer their own advice or opinion, but help the individual find their own solution”. It is important for a manager to identify if somebody needs a mentor or a coach according to what stage that person is in.

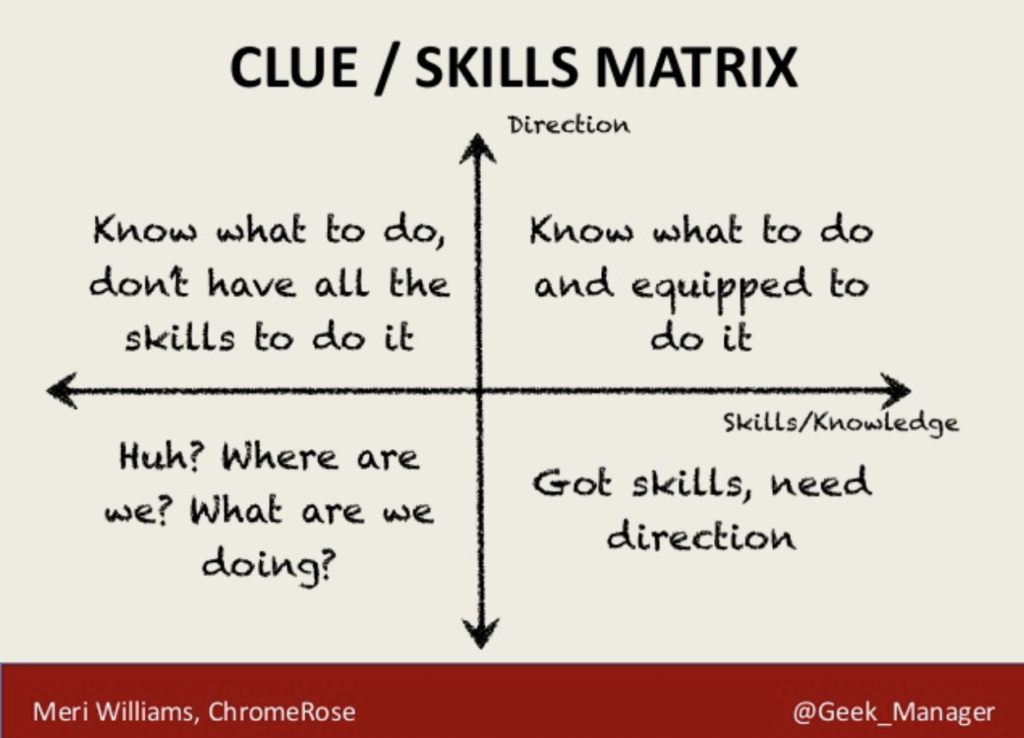

The amazing Meri Williams explains this very well through what she calls the “clue/skills matrix” (an adaptation of the situational leadership model):

In practice, when people know what to do but lack the skills, they need a mentor. If they have the skills but don’t know what to do, they need a coach. If they are at the upper-right corner of the matrix, your only job is to be a “bulldozer” and make sure they have a free road ahead to do their job.

If you cannot be a mentor (maybe you’re not entirely familiar with the domain that person is working on) then it should be your job to find a good mentor for them.

Be a shit umbrella… but with some holes!

In management, there is a well-established concept that the manager should be a “shit umbrella”: in turns, they should shield the team from all the distracting shit that happens above them (being politics, insensitive comments or just demands that have no place at that time). I agree with that, but I also think it is necessary for them to be exposed a tiny bit to the harsh reality outside the team cocoon. This way, they can learn what expects them when they progress in their careers and they can grow stronger.

Best practices: what helped me so far

A management role does not come with an instruction manual! Every team is different, because every individual is. But there are certain techniques that have helped me during my manager’s career:

- Regular one-on-ones:

I won’t go into details about one-on-ones since there’s plenty of great suggestions online on how to make an effective one-on-one (for example here and here). But I cannot stress enough how important it is to have regular one-on-ones with your team. Just remember: one-on-ones are not a status update. The most important thing I get out of a one-on-one is how that person feels, if they’re happy with the work and the team and what I can do to improve their life in the company. - Onboarding guide:

It is important to keep a document for new hires to speed up the onboarding process for your team. This should give an overview of the team’s scope, what each person in the team is responsible for, the tooling and processes used, general “team rules” (e.g. core hours, working from home, how to request annual leave, training budget) and any knowledge you think it is appropriate to acquire while ramping up. - Team retros:

Retros are essential to understand what is working and what not. I suggest setting aside an hour every fortnight for it. There are also tools and platforms that can help you with that, for example, Peakon or the retrobot for Slack. Anyway, you’ll be surprised to find out that even when things are going smoothly there’s always something that can be improved – most of the time it was in front of you but you didn’t notice! - Document gardening:

Every team owns documentation. May it be technical like feature specifications, may it be about processes or roadmaps: there will always be a set of documents that need periodic updates. I suggest that everyone in the team (especially the manager) set aside some time (half an hour a week?) in their calendar to update the documents they own. Because technical debt is not only about software!

In conclusion

Thinking back, I can now see why that third parrot was so important even though it wasn’t explicitly speaking in other languages or doing maths. Or maybe I’ve just badly misread a kids’ joke, but hopefully, you still got something out of this reading 🙂

1,290 total views, 1 views today